Opioids are key in treating opioid addictions, doctor says

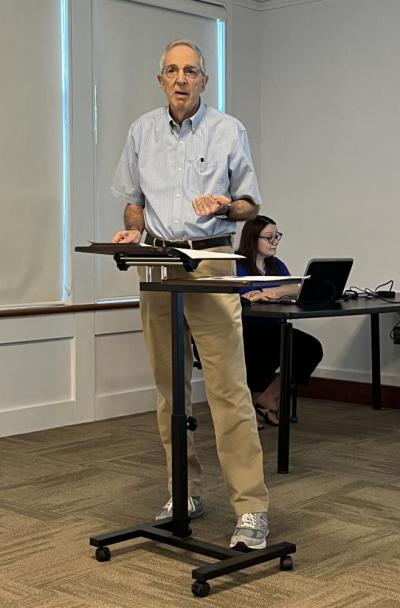

LAKEVILLE — Opioids, it turns out, are one of the best ways to treat opioid addictions, according to local physician Bob Friedman.

Friedman, who has specialized in treating patients with substance use disorders over the last eight years, shared this information during a presentation at the Lakeville Public Library on the evolution of the opioid crisis on Tuesday, Aug. 20.

“Opioid use is a brain disease,” and needs to be “treated like a brain disease,” said Friedman.

Opioid use increases the amount of opioid receptors in the brain, and, “those receptors are not happy unless they’re full,” explained Friedman. “That’s what leads to addiction.”

Friedman described the case of one patient he works with that takes a drug called buprenorphine to treat her addiction.

Buprenorphine “is an opioid,” said Friedman. While Buprenorphine fills the brain’s opioid receptors, “you don’t get high from it,” so it’s not addictive, he said.

It is also an effective way to prevent overdoses, because it doesn’t attack the brain’s respiratory system, as other opioids do. Friedman said that what kills people after an overdose is the fact that they stop breathing.

Using opioids like buprenorphine or methadone to treat opioid addiction is a practice called Opioid Agonist Theory, according to the Centre for Addiction and Mental Health. These drugs prevent withdrawals and reduce cravings for opioid drugs.

During the presentation, Friedman showed a graph illustrating that people who took opioids such as buprenorphine or methadone to treat their addiction were much less likely to relapse than those who didn’t take opioid medications during treatment.

Friedman shared how most of the patients he treats with buprenorphine “are doing really well.”

Three hundred people a day die from opioid overdoses, he said. “If a plane crash killed 300 people, you’d think they’d be doing more about it than they are now,” he said.

Most people who get hooked on opioids are not recreational drug users, said Friedman. The majority, around 60%, get addicted as a result of a medical problem or work-related injury.

Around 30% are recreational drug users who then get addicted to opioids, he added.

The tough love approach of kicking addicts out on the streets doesn’t work well, said Friedman, especially with the increased risk of an overdose due to the prevalence of pills laced with fentanyl.

“Before [an opioid addict] hits rock bottom, they might be dead,” he said.

Having supportive family and friends, he said, “is the way to get people better.”