Researchers talk PFAS and how residents can avoid them

MIDDLEBORO — In 2024, Middleboro declared that one of its largest public wells tested above a new state standard for the concentration of PFAS, or perfluoralkyl and polyfluoroalyl substances, in water. Since then, forever chemicals have been a concern for residents.

At last year’s April Town Meeting, the town took a step to mitigate the impact of PFAS on drinking water by appropriating $33 million for a new treatment plant, according to Kimberly French, the board president of Sustainable Middleboro. Construction on the plant is slated to start this summer.

The town also plans to spend $100 million over the next five years on mitigation, with the goal of achieving non-detectable levels in drinking water, French said.

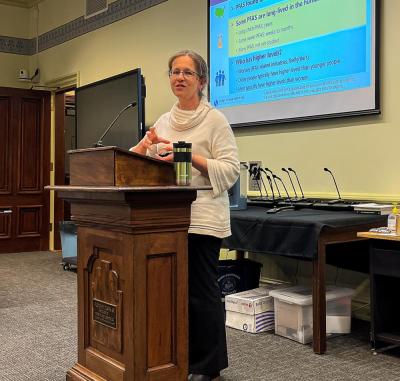

On Wednesday, April 2, researchers from the Silent Spring Institute and Clean Water Action visited Middleboro Town Hall to explain what PFAS are and offer tips for how people can avoid them.

PFAS is an umbrella term for the over 14,000 different chemical structures that have carbon-flourine bonds, which are the strongest bonds in organic chemistry and have a high electronegativity, which means they are resistant to degradation.

PFAS are man-made chemicals often used in stain resistant, water resistant and non-stick materials that can withstand heat without degrading and can resist undergoing chemical reactions or decomposing.

“These are all negative chemicals, and once they get into the environment, they don’t really break down,” said Laurel Schaider, a senior scientist at the Silent Spring Institute, a nonprofit research organization that strives to understand the links between everyday chemical exposures and women’s health.

PFAS are also considered forever chemicals because of their “extreme persistence,” which Schaider said is due to their carbon-flourine bonds.

“They’ve been found in every corner of the globe. They’ve been found in rain water and ocean water. They’ve been found even in the blood of polar bears. So these have really become global contaminants,” Schaider said.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention conducted a study that found that over 99% of people tested had some level of PFAS in their bloodstream, Schaider said.

“All of this put together is really concerning because from what we’ve learned so far, there’s overwhelming evidence that PFAS can be harmful to our health,” she said.

According to a study from the Environmental Working Group, it’s estimated that 200 million Americans have PFAS in their tap water.

And while PFAS are found in many items including carpets, dental floss, fast food wrappers and cookware, Schaider said that knowing there are PFAS in water is “really sounding the alarm.”

“I think there’s something different about drinking water,” she said. “It really resonates with people to learn that their water, which they assume is pure and … has these toxic chemicals.”

While PFAS have been used in consumer products since the 1950s, it wasn’t until 10 to 15 years ago when analytical labs could measure the concentration of PFAS in parts per trillion that alarm regarding health concerns rose.

“In communities where there’s drinking water contamination, people in those communities can have elevated levels of PFAS in their blood,” Schaider said.

Older adults often have higher levels of PFAS in their blood than those younger because the chemicals accumulate over time and men tend to have higher levels than pre-menopausal women. Infants can also be exposed to PFAS during pregnancy and through breast milk.

“All of this put together is really concerning because from what we’ve learned so far, there’s overwhelming evidence that PFAS can be harmful to our health,” Schaider said.

A series of studies conducted showed that children with higher exposures to PFAS had less of an antibody in response to routine vaccinations, Schaider said.

Clean Water Action passed a bill recently to restrict PFAS in firefighter protective gear after finding that firefighters have been getting cancer at elevated rates, which Laura Spark, the environmental health program director at Clean Water Action, said was in part due to PFAS.

“PFAS are used in hundreds of different things, and we can’t actually fully avoid them,” Spark said.

She explained this was due to the presence of PFAS in manufacturing, including building materials, medical devices and pharmaceuticals.

Residents can treat water in their homes to remove PFAS with activated carbon filters or solid carbon block filters, which can be purchased online, or through a reverse osmosis system.

Other ways to avoid PFAS are eating more fresh foods, avoiding food packaging, questioning whether something needs to be stain-resistant and avoiding microwave popcorn, which can be packaged in bags coated with PFAS.

The websites PFASCentral.org and the Environmental Working Group’s website list alternatives to PFAS containing products, including alternative rain gear and cookware options.